The Hero from Across the Sea

From the online book: Music Through the Centuries by Don Robertson (2005)

Published on DoveSong.com – Revised and expanded in 2016 and 2023

Chapter Six – The 20th Century: “Dissolution”

Then, in the midst of it all, came a hero from across the sea, his armor burning brightly in the sun…

North Indian Classical Music

I would like to tell you how I discovered the Classical music of North India. I was studying music at Colorado University in 1965 when I met a young man from Australia named Richard O’Sullivan at an audio and record store in Boulder. We became friends. While my studies at the music school at Colorado University focused on more traditional music, it was here, in this store, that Richard introduced me to the major contemporary composers of the time: Boulez, Berio, Nono, Castiliani, Schockhausen, Cage, to name but a few. He was always very excited about their music. I was actually learning more about music from him than I was from my classes in the music school except for a semester of Music Appreciation, taught by a grad student, where I found out about Renaissance sacred music and Gregorian chant.

Late one night he called me from the store and begged me excitedly to come immediately. He had something he wanted to play for me, but he wouldn’t tell me what it was. Obligingly, I got into my car and drove to the store. It was well past closing time. He seated me carefully in the room where during business hours audio speakers and hi-fi components were demonstrated.

He then carefully placed the arm of one of the record turntables onto a record. He was grinning with the anticipation of how I might react.

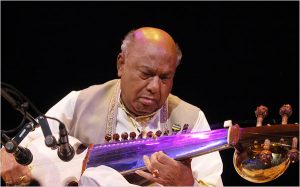

I expected to hear another Boulez masterpiece of colorful discords, or perhaps a new serial piece by Luigi Nono. But as new sounds poured from the speakers, they were like none I had heard before, and they were instantly captivating. I was listening to the master sarod player from India, Ustad Ali Akbar Khan.

Thus, I began a journey that I have traveled, even to this day. I left Colorado University to pursue the study of this newly found music, finally arriving in Los Angeles, where I began learning the sitar from Harihar Rao. Harihar played sitar and tabla and had moved to the USA in 1964. The sitar, like the sarod, is a North Indian classical music stringed instrument.

The following year, I moved to New York, and there I began studies with Ustad Ali Akbar Khan himself. By this time, every note from each of the very few records that had been available in America, I already knew by heart.

I was not alone, as classical music from North India would have an enormous effect on music in the West: a fact that has been too little acknowledged.

As the situation in American and European concert halls continued to deteriorate due to the continued onslaught of discordant music, an important figure arrived from India. His name was Ravi Shankar, a musical diplomat that awakened the West to his ancient and great tradition of classical music, one that had been developing in a parallel course with ours: the classical music of Northern India, one of the greatest musical traditions of the world.

It came heroically to our aid and helped transform three of the major genres of Western music: rock, jazz, and classical music… all three deeply affected by this ancient music from North India, a fact that has not often been fully understood. Most people still do not know what North Indian classical music is.

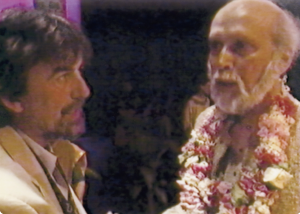

Ravi Shankar was a dancer who became a musician, studying with the great musician and teacher Allauddin Khan, Ustad Ali Akbar Khan’s father. Ravi began traveling to the West in early 1960s, and in 1966 George Harrison of the Beatles became his student. Following this, Ravi became a celebrity, stealing the show at three major rock festivals: the Monterey Pop Festival, the Concert for Bangla Desh, and the famous Woodstock Festival.

Ravi Shankar inspired changes in the three major forms of Western music.

The Influence on Popular Music

The influence of North Indian classical music on popular music first occurred with the release of the song “Norwegian Wood” in December 1965 on the Beatles’ Rubber Soul album, on which George Harrison played the sitar. George had been interested in North Indian classical music since discovering the sitar during the summer. The following year, Harrison’s song “Love You To”, recorded in April of 1966, was “all out” North Indian, introducing both sitar and tabla. It was released in August on the album Revolver. Author Jonathan Gould describes the song’s slow sitar introduction as “one of the most brazenly exotic acts of stylistic experimentation ever heard on a popular LP.”

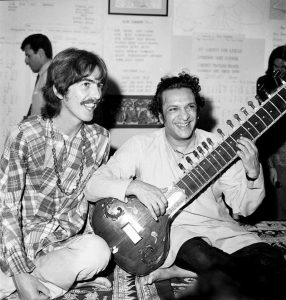

Two months later, George met Ravi Shankar and became his student. The music of the Beatles changed considerably after the connection with Ravi Shankar. In September, George and his wife spent six weeks in India while George studied with Shankar.

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

1966 was also the year when North Indian Classical music influenced American popular music. The Los Angeles band, the Byrds, who had a hit recording the previous year with Bob Dylan’s song “Hey, Mr. Tambourine Man”, had been listening to Ravi Shankar recordings on their tour bus and released the Shankar-influenced “Eight Miles High” in March of 1966. In May, the Rolling Stones released “Paint it Black”. The group’s guitar player, Brian Jones, who played sitar in the recording, had studied sitar with Harihar Rao. Both “Eight Miles High” and “Paint it Black” were big hit songs.

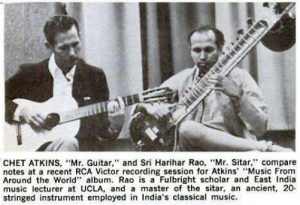

World Pacific Records in Los Angeles then recorded an album addressing the North Indian/American popular music trend. It featured Harihar Rao on sitar. It was called Raga Rock by The Folkswingers, Featuring Harihar Rao, and it contained covers of “Norwegian Wood”, “Paint it Black” and “Eight Miles High”, along with some of the hit rock songs of the time such as “Along Comes Mary” and “Hey Joe”. This album gave birth to the name of the subgenre called to this day, “Raga Rock”. That year, Harihar also played on the famous country-music guitarist Chet Atkins’ It’s a Guitar World album.

In September of 1966, I moved to New York City. Harihar had written an instruction book for the sitar called Introduction to Sitar, the first sitar instruction book in the English language. He had asked me to help with the publisher who was located in the Brill Building in New York City.

People who worked for the publisher of Harihar’s book introduced me to the owner of Carroll Musical Instrument Rentals nearby, and there I met musicians who helped me become a studio musician, specializing in the instruments of North Indian classical music.

In early 1967, I was given the opportunity to play the drone instrument of North Indian classical music called the tamboura on Alan Lorber’s Lotus Palace album with Collin Walcott, who played both sitar and tabla. Collin was a sitar student of Ravi Shankar and tabla student of Alla Rakha, Ravi Shankar’s accompanist. Collin went on to play sitar and tabla with the group called Oregon. Lorber’s Lotus Palace was the second album of pop music that covered pop songs using North Indian classical music instruments.

During the first session for the album, Collin and I showed curious session guitarist Vincent “Vinnie” Bell Collin’s sitar and my tamboura. Vinnie carefully looked over Collin’s sitar, and then subsequently, in partnership with Danelectro, invented the “electric sitar,” which he proudly showed us not long after the Lotus Palace sessions. Vinnie’s electric sitar was popular with studio musicians and was featured on many popular music tracks, such as “Green Tambourine” by The Lemon Pipers (1967), “Cry Like a Baby” by The Box Tops (1968), and the love theme from the 1970 film Airport, becoming a familiar sound in rock and popular music.

(Universal Newsreel, September 1967)

The group called The Doors’ first album was released January 4th, 1967. I saw the album in the window of Sam Goody’s record store in NYC and bought it out of curiosity. When I listened to the song “The End” written by the guitarist Robby Krieger, I was amazed at the level of North Indian classical music influence. I didn’t know it at the time, but like myself, Robby had been studying with Harihar Rao in Los Angeles together, with the Door’s drummer John Densmore. Weeks after the I bought the album, I went to see The Doors at Steve Paul’s Scene in New York. There were only about twenty people in attendance. Ukulele-strumming Tiny Tim was a solo act that took the band’s place during their break, while Jim Morrison sat at the table next to mine chatting with friends. I thought that the band would continue the Indian music trend in later albums, but they didn’t. The evolution of the Doors after that first album was, in my opinion, nothing of much value.

In May 1967, the Beatles released the album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band that included the song “Within You Without You”. It was another George Harrison, North Indian classical music-influenced song.

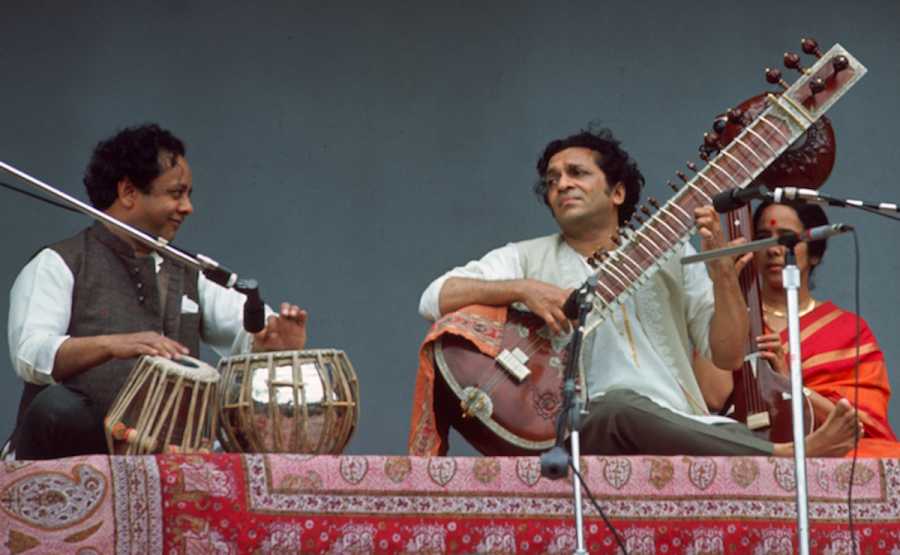

Ravi Shankar had an enormous influence on music. His appearance with tabla maestro Alla Rakha at the Monterey Pop Festival in June 1967 was a monumental event. The response from the audience was thundering acceptance, much greater than the stunned looks given Jimi Hendrix when he set his guitar on fire at the same event. Ravi Shankar provided a gift from India to the West. He influenced the Beatles, John Coltrane, Philip Glass and many others. Yet even now his influence continues, as he is the father of multi-Grammy-award-winning singer and pianist Nora Jones.

The Influence on Jazz Music

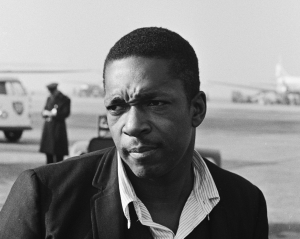

John Coltrane had begun listening to Ravi Shankar in 1961. “I collect the records he’s made, and his music moves me. I’m certain that if I recorded with him, I’d increase my possibilities tenfold, because I’m familiar with what he does, and I understand and appreciate his work. I also hope to meet him when I return to the United States,” he told François Postif in France. Ravi and Coltrane met in December of that year and became friends. The Coltranes, John and Alice, named their second son after Ravi in 1965. “I like Ravi Shankar very much. When I hear his music, I want to copy it – not note for note of course, but in his spirit. What brings me closest to Ravi is the modal aspect of his art,” John said later.

Coltrane’s understanding of North Indian classical music was only rudimentary, and his familiarity with it apparently went no further than Ravi Shankar. But the scales that he became familiar with influenced his music considerably, and in turn influenced the course of jazz.

Jazz trumpeter Don Ellis was a Harihar Rao student. Together with Harihar, he founded the Hindustani Jazz Sextet in 1964 and performed in the famous Los Angeles area jazz clubs Shelly’s Manne-Hole and Howard Rumsey’s Lighthouse in Hermosa Beach (clubs in which I had hung out three years previously).

There were a number of jazz artists who were influenced by or incorporated aspects of North Indian classical music in their music during the 1960s. The most notable was the jazz flautist Paul Horn. He went to India in 1967 and recorded two albums with India musicians performing North Indian ragas: Paul Horn in India, and Paul Horn in Kashmir. He made a second trip to India in February 1968 to study transcendental meditation with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. A number of celebrities were in attendance, including the Beatles. He recorded playing his flute in the Taj Mahal on that trip and released the music in an album called Inside in the summer of 1969. It sold over a million records.

Paul Horn’s Inside is now considered to be, along with Tony Scott’s Music for Zen Mediation of 1965, the first “new age” record albums, a label that was applied only in the 1980s to the genre of ambient music influenced by India and world music. However, neither album was considered to be new-age music at the time of their release.

The Influence on Classical Music

The influence on the classical music of the Western world is covered in my article “The Return of Tonality in Classical Music,” next in this series of articles from my online book “Music Through the Centuries.”